Rethink Zambia’s natural resources regeneration policy

Notice: Undefined index: catFilterList in /home/zambi/public_html/wp-content/plugins/wp-likes/api.php on line 243

Sebastian Scott, with his friend and co-founder of the Grassroots Trust in Zambia, Rolf Shenton. The aim of the trust is to protect and develop traditional farming systems that help small-scale farmers to farm profitably and sustainably with minimal input costs.

Few can deny that Zambia is ever more dependent on mining resources while renewable natural resources are bleeding profusely and agriculture is on the decline. This begs the question as to what happens to the economy when our finite mining resources peak and begin to reduce and eventually run out?

In 2010, Paul Collier, an economist and professor at Oxford University published “The Plundered Planet: Why We Must—and How We Can—Manage Nature for Global Prosperity”. In it he addresses the critical intersection of environmental sustainability, natural resource management, and global economic development.

In 2010, Paul Collier, an economist and professor at Oxford University published “The Plundered Planet: Why We Must—and How We Can—Manage Nature for Global Prosperity”. In it he addresses the critical intersection of environmental sustainability, natural resource management, and global economic development.

Collier argues that natural resources, such as oil, minerals, and forests, are both a potential source of wealth and a potential curse for developing nations. Poor management of these resources often leads to environmental degradation, economic inequality, and ultimately political instability—a phenomenon known as the “resource curse.” Collier contends that the plunder of these resources, whether through exploitation by foreign entities or mismanagement by local governments, undermines a country’s prosperity and exacerbates poverty.

Collier argues that natural resources, such as oil, minerals, and forests, are both a potential source of wealth and a potential curse for developing nations. Poor management of these resources often leads to environmental degradation, economic inequality, and ultimately political instability—a phenomenon known as the “resource curse.” Collier contends that the plunder of these resources, whether through exploitation by foreign entities or mismanagement by local governments, undermines a country’s prosperity and exacerbates poverty.

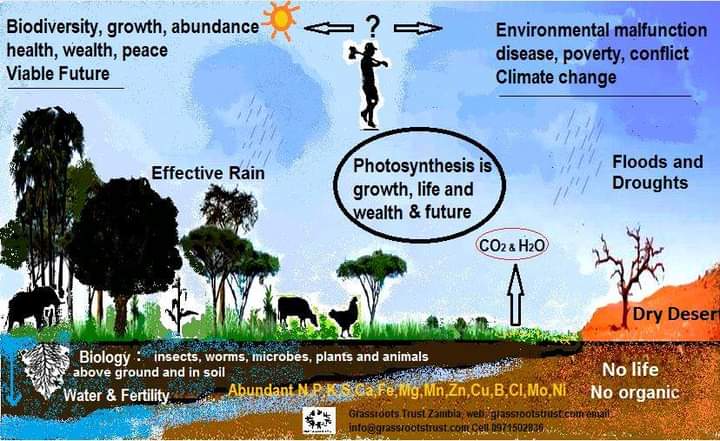

Looking at the patterns and trends over the past decades, Zambia seems to fit the ‘resource curse’ fairly well. We see increased dependence on mining and ‘cashing in’ of forest and other soil-based resources while agriculture, the production of food fibre and energy from land and waters, is being steadily undermined by environmental malfunction, essentially biodiversity loss leading to desertification and climate change.

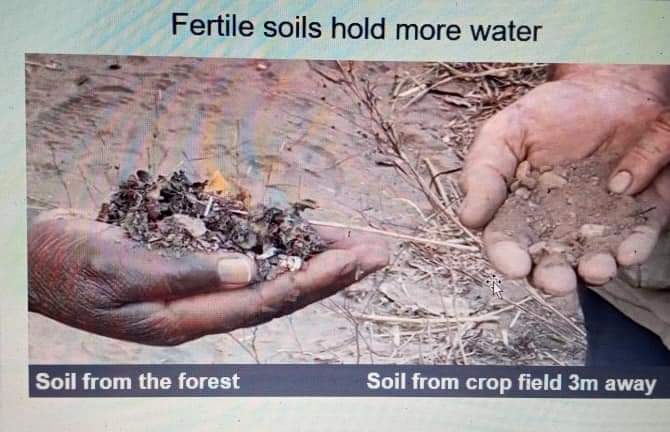

This rainy season we have seen massive soil loss across the country as rains finally poured onto bare ground, carrying tonnes of precious top soil from each hectare of land to the waterways. Sure, as the rains stabilised in the new year vegetation returned and floods were less noticeable, but anyone who has observed the trends closely will acknowledge that things are getting steadily worse on the land, leading to a general decline in fertility, water retention and productivity.

This rainy season we have seen massive soil loss across the country as rains finally poured onto bare ground, carrying tonnes of precious top soil from each hectare of land to the waterways. Sure, as the rains stabilised in the new year vegetation returned and floods were less noticeable, but anyone who has observed the trends closely will acknowledge that things are getting steadily worse on the land, leading to a general decline in fertility, water retention and productivity.

The environment is also subjected to increasing number of shocks from bad mining, the latest, a catastrophic failure of the main tailings dam at Chambishi causing enormous damage to the Kafue river, the extent of which we are yet to fully understand. More and more manganese and gold mines all over the country are spewing pollutants out into the atmosphere and rivers.

Collier, who spend years advising many African governments, critiques both the unchecked exploitation by corporations and the misguided policies of environmentalists who oppose all resource extraction, arguing that both extremes are detrimental to sustainable development.

Collier, who spend years advising many African governments, critiques both the unchecked exploitation by corporations and the misguided policies of environmentalists who oppose all resource extraction, arguing that both extremes are detrimental to sustainable development.

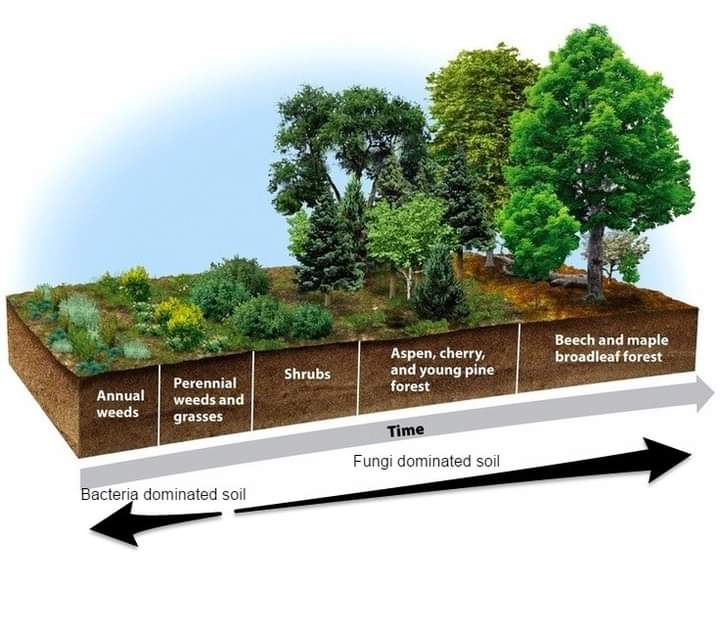

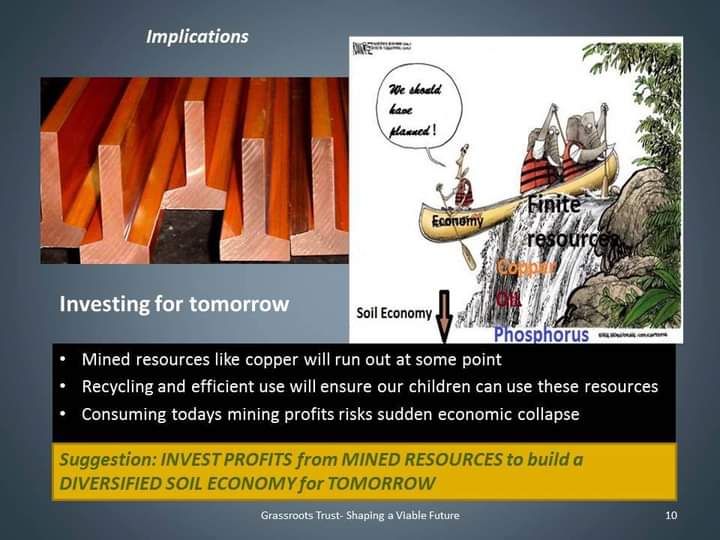

Essentially what he argued was that as finite resources begin to decline the soil economy would have to take up the slack and eventually replace all the goods and services we consume today using money from minerals. If the soil economy continues its current decline, we are setting ourselves up for a catastrophic collapse.

Collier proposed practical solutions for managing natural resources responsibly. He emphasized the importance of good governance, transparency, and international cooperation. Key ideas include:

– Creating systems to ensure that resource wealth benefits the entire population, not just elites.

– Implementing global standards for resource extraction to prevent environmental destruction.

– Stop consuming profits from finite resources; rather invest them into building a soil-based economy that can sustain human civilisations for millennia to come.

Imagine how reliant on fossil fuels we are right now not only for transport, but also for food production in terms of machinery, fertiliser, chemicals and increasingly, energy for water pumping. What Collier is saying is that by the time fossil fuels peak and become uneconomical, our economies must be able to transition smoothly to producing all this food, fibre and energy organically.

Imagine how reliant on fossil fuels we are right now not only for transport, but also for food production in terms of machinery, fertiliser, chemicals and increasingly, energy for water pumping. What Collier is saying is that by the time fossil fuels peak and become uneconomical, our economies must be able to transition smoothly to producing all this food, fibre and energy organically.

This is a call to action for policymakers, businesses, and citizens to rethink how we use and regenerate Zambia’s natural resources, to ensure we avert a sudden collapse. All my articles have shared ideas on how we can achieve this while continuing to improve the quality of life for every citizen.

This is a call to action for policymakers, businesses, and citizens to rethink how we use and regenerate Zambia’s natural resources, to ensure we avert a sudden collapse. All my articles have shared ideas on how we can achieve this while continuing to improve the quality of life for every citizen.