Notice: Undefined index: catFilterList in

/home/zambi/public_html/wp-content/plugins/wp-likes/api.php on line

243

Post Views: 2,032

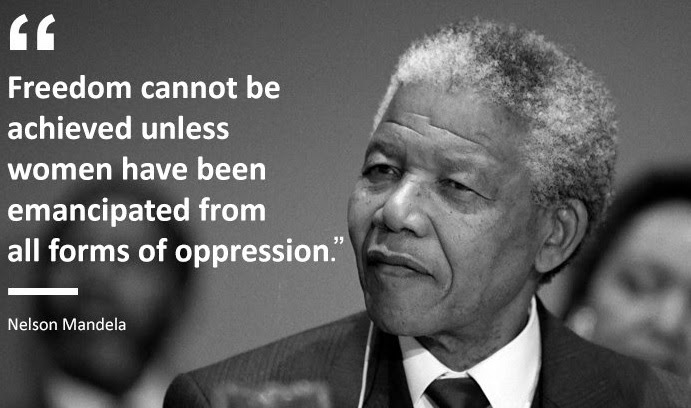

Mandela, the gender activist who never stopped learning

By Colleen Lowe Morna – CEO of Gender Links. This article is written in her personal capacity).Photo courtesy of UN Women

Monday 9th July 2018: There is a scene still etched in my memory from my younger days as a reporter. Soon after his release from jail in 1990, Mandela paid an official visit to Zimbabwe as leader of the African National Congress (ANC). As he emerged from the flight, a group of South African women in exile broke forth from behind the barrier shouting “Comrade Nelson!”

They embraced and kissed him, in a show of affection and patriotism that transcended time, place, local norms and culture. Visibly uncomfortable, the host, now ex-President Robert Mugabe, stood stiffly at a distance, barely managing a smile. Moments later, the two men walked down the red carpet and onto cloths bearing Mugabe’s image that had been laid on the ground by kneeling women, the party faithful of the ruling Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU). Then it was Mandela’s turn to show extreme discomfort.

There is a saying that no nation ever rises above the extent to which it holds women in bondage. It follows that the attitude of our overwhelmingly male leaders towards their female compatriots must be one of the key yardsticks of their leadership.

Retired Constitutional Court Judge Albie Sachs, in an article on Mandela’s 85th birthday, commented on the tremendous strides made by Mandela, from the days when he would say things like “no man worth his salt” should accept certain terms of the constitutional negotiations, to becoming the husband of a woman who did not bear- nor want to bear – his surname.

Mandela’s little – commented upon “gender journey” is one of the more amazing stories of his life. As activists, we quote repeatedly from Mandela’s opening of parliament in 1994: “Freedom cannot be achieved unless women have been emancipated from all forms of oppression.” We recognise the strides that Mandela has made from old school patriarch to a modern husband in his third marriage to Graca Machel, wife of the late Mozamican president Samora Machel, who retained the name Machel, and negotiated a “commuter marriage” given her base and interests in Mozambique.

Yet, as I read through the various accounts of Nelson Mandela’s life, I find only one interview that has dared to be brutally honest about his fallibility. Following his release from jail in 1994, Mandela’s late first wife Evelyn Mase commented: “How can a man who committed adultery and left his wife and children be Christ? The whole world worships Nelson too much. He is only a man!” What set Mandela apart is that unlike most leaders he accepted his inadequacies, pleading constantly that he was no saint. As he put it: “the greatest glory in living is not in falling, but in rising every time we fall.”

Nelson Mandela, whose wandering eye is not one of his more exemplary legacies, married three times. After divorcing Evelyn, he married Winnie, a strong but controversial leader whom he would divorce after his release from prison on grounds of alleged infidelity. But in another sub-plot of the Mandela drama, two women – one dead and one alive – have claimed to be Mandela’s children through liaisons during his marriage to Winnie.

Onicca Nyembezi Mothoa resurfaced just before Mandela died, demanding to meet her father. The splitting image of Mandela, Mothoa was shut out by the family, despite her plausible story of the relationship that her mother had with Mandela at the height of the anti-apartheid struggle and willingness to take a DNA test. In a country where single mothers raise 40% of children this does little to assist campaigns for responsible fatherhood.

Mase’s daughter Makaziwe and grandson Mandla were at the epicentre of a “grave” fight over where to bury the remains of Mandela before he died. Money loomed large in the controversy. Ranked in the same league as Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King, tourism experts reckoned that wherever Mandela was laid to rest will dwarf Elvis Pressley’s Graceland that receives 600,000 visitors annually, in its crowd-pull and revenues.

Commentators were at pains not to visit the sins of the children on the father. Brand specialists assured the public that the Mandela name would remain in-tact: no matter what.

Few questioned the root cause of the dispute – the fact that Mandela, without question, bequeathed his legacy to his grandson Mandla after his two sons died, by-passing his oldest daughter Makaziwe. A gender aware critique of Mandela’s legacy needs to question whether this legacy would not have been safer in the hands of an older daughter than of an ill prepared younger grandson.

Sociologists and psychologists reminded us of the effect of the “absent father” – Mandela’s 27 years in jail. Not being able to provide for his family during 27 years of incarceration must have weighed heavily on Mandela’s sense of “manhood”. While gender equality gradually started to hit the radar in the world outside, one wonders how much of that filtered through the iron bars of Robben Island.

Mandela emerged to the personal tragedy of his second marriage. Yet, whatever his differences with Winnie Mandela, he showed the utmost personal respect for her and her contribution to the struggle. Mandela’s third marriage to Graca Machel took him a step further in his journey towards understanding gender equality.

She is from another country, Mozambique. She is the only woman in the world to have been a “first lady” twice. She is her own person; some speculate that she has political ambitions of her own in Mozambique. Theirs was a commuter marriage- they spent equal amounts of time at each other’s homes. They shared common humanitarian interests. Yet they had their own distinct schedules. They were equals in a caring, mutually supportive relationship.

Mandela once joked that in his next life he would send Machel to take cooking lessons. He knew of course that what he meant was in his last life! For as his personal gender journey evolved, Mandela set bold precedents for women in public life in South Africa that when “herstory” is written will surely be one of his largest footprints.

It is a well- known fact in African National Congress (ANC) circles that Mandela tried to push for a fifty percent quota for women in the elections, settling for thirty percent when it became apparent that the latter would not fly.

He was the African president to take the bold move to head hunt promising women and put them in his cabinet, setting a trend that no South African president would dare reverse. Mandela lifted the South African cabinet from less than two percent to 30% women by the time he stepped down in 1998 – many deputy ministers who went on to be ministers. Fast forward to 2018 when President Cyril Ramaphosa became the first South African president to get the gender balance in his cabinet just right (though his deputy is a man).

There are many examples of outstanding South African women who Mandela talent spotted. One example is Geraldine Fraser-Moleketi, Mandela’s one time personal assistant, whom he made deputy minister of social development in his first cabinet. She went on to become minister of the Public Service, pushing an ambitious reform programme that went a long way towards creating gender parity in South Africa’s bureaucracy. She later served as Special Envoy on Gender to the African Development Bank, and is now Chancellor of Nelson Mandela University. Her inspirational example speaks volumes of the “enabling environment” that leaders can create for gender equality to blossom.

Mandela’s legacy is not just the space he created for South African women to participate in public life and as citizens. It is his understanding of leadership. In one of her reflections on Madiba, Graca Machel observed that the difference between her husband and other politicians is that when he kissed babies he did so not for the cameras, but because he cared. There is much discussion in the study of leadership about the difference between IQ- intelligence quotient, and EQ- emotional quotient. Most leaders come with a fair dose of the former. Mugabe, with six university degrees, is a case in point. He was clearly a clever politician. But he was a dismal leader.

Mandela’s legacy is not his brilliance. His legacy is his high EQ. It is why, for example, he saw beyond the petty politics that haunted the fight against HIV/AIDS towards what has to be done. People were at the centre of his understanding of politics. He led from the heart, and not from the head. It does not take much IQ to figure out that EQ is an extremely rare ingredient in world politics and leadership, especially in this era of the Donald Trumps and Vladimir Putins; not to mention our own array of African strongmen. Studies show that, because of their socialisation, women tend to be much higher on EQ than men. The fact that women are still sorely under-represented in decision- making is possibly one explanation for global leadership styles that are so lacking in that basic ingredient of care.

Let us take three lessons from Nelson’s Mandela’s life. One is to challenge our own socialisation, as he did, by striving for equal representation and partnership between women and men. The second is to feminise our understanding of leadership- the real secret behind the miracle that is Mandela. The third is to never stop learning.

I recall, as founding CEO of the Commission on Gender Equality, handing over the Commission’s first report, together with commissioners and staff, to the then President Mandela at Union Buildings in 1997. As he walked in the room, Mandela expressed his pleasure at being among so many “beautiful” women. One of my younger staff at the time had the courage to raise her hand and say, “Mr President that is not what this commission is about!” He paused, looked around, and responded: “You are so right! I am still learning!”

That, Mr President, is why you will always be my hero!

(Colleen Lowe Morna is CEO of Gender Links. This article is written in her personal capacity).Photo courtesy of UN Women

Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela was born on 18 July 1918 in Mvezo, Umtata (now Mthatha), Transkei, South Africa. He had thirteen siblings by the same father, and two mothers. … On his first day of school, he was given the name Nelson by his teacher Miss Mdingane.

https://simple.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nelson_Mandela

Mandela, the gender activist who never stopped learning

Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela was born on 18 July 1918 in Mvezo, Umtata (now Mthatha), Transkei, South Africa

Be the first to like.

Be the first to like.